At a time when boys dream of going to university, entering adulthood, finding jobs, of love and marriage, Jayalath Bandara ended in prison. Not just in prison, but in death row, and he’s been languishing there for the past eight years.

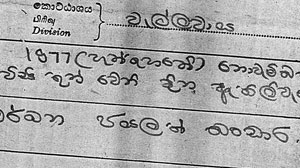

The horror of his situation strikes home with all the more force when you realise that Bandara now 34 is confined to a wheel chair. He has to be helped by his elder brother, jailed along with him and fellow prisoners. If the day comes when the death sentence is actually carried out, he’ll have to be hung while sitting on that chair. Or he’ll have to be held up by two guards while the hangman tightens the noose around his neck.It’s a gross miscarriage of justice. Bandara isn’t a hardened criminal incarcerated here for a shocking crime. He can only be described as an accessory to a murder. He was standing by his father and brothers who were arguing with another villager over the right to work a paddy field. The argument went bad and Jayalath’s elder brother Chandraratna Bandara killed the man with a mamoty. The police arrested all the males in the family including Jayalath who was a 17-year-old schoolboy. That was in March 1994. The judge, reluctant to jail a minor, released him on Rs.2,000 bail. The police seem to have been prejudiced against the family from the start and Jayalath and his terrified mother were forced to sign a statement at the Wellawaya police station, the contents of which were not shown to them. It was while being at liberty on bail in 1996 that Jayalath fell from a coconut tree, damaging his spine. After the initial treatment, recovery seemed possible, but the trial interrupted treatment and he ended up being a cripple for life.

The case was heard at the Badulla Magistrate’s Court. The defense lawyer abandoned the case a few weeks before the verdict. Clearly, the defense had not studied the case properly. The judge had not been informed of the vital fact that Jayalath was only 17 and hence a minor when the murder was committed. The result was a gross miscarriage of justice as far as Jayalath was concerned. A group of volunteers are now acting to get Jayalath a presidential pardon. The sooner this happens, the better, because it is inhuman to keep this young man in jail. To understand the meaning of this statement, you really have to see how he survives on death row. Words alone aren’t enough to reproduce the full horror of his situation.

He spends most of his time in Bogambara Prison, Kandy, but is sent to Welikada prison in Colombo for two-week stints. It isn’t much of a choice. Death row at Bogambara is hellishly hot with all windows covered, but there are fewer mosquitoes at night due to the milder climate. It is also cleaner than the pest-infested death row at Welikada, though the word hardly seems applicable to the dismal interiors of our overcrowded prisons.

The horror of his situation strikes home with all the more force when you realise that Bandara now 34 is confined to a wheel chair. He has to be helped by his elder brother, jailed along with him and fellow prisoners. If the day comes when the death sentence is actually carried out, he’ll have to be hung while sitting on that chair. Or he’ll have to be held up by two guards while the hangman tightens the noose around his neck.It’s a gross miscarriage of justice. Bandara isn’t a hardened criminal incarcerated here for a shocking crime. He can only be described as an accessory to a murder. He was standing by his father and brothers who were arguing with another villager over the right to work a paddy field. The argument went bad and Jayalath’s elder brother Chandraratna Bandara killed the man with a mamoty. The police arrested all the males in the family including Jayalath who was a 17-year-old schoolboy. That was in March 1994. The judge, reluctant to jail a minor, released him on Rs.2,000 bail. The police seem to have been prejudiced against the family from the start and Jayalath and his terrified mother were forced to sign a statement at the Wellawaya police station, the contents of which were not shown to them. It was while being at liberty on bail in 1996 that Jayalath fell from a coconut tree, damaging his spine. After the initial treatment, recovery seemed possible, but the trial interrupted treatment and he ended up being a cripple for life.

The case was heard at the Badulla Magistrate’s Court. The defense lawyer abandoned the case a few weeks before the verdict. Clearly, the defense had not studied the case properly. The judge had not been informed of the vital fact that Jayalath was only 17 and hence a minor when the murder was committed. The result was a gross miscarriage of justice as far as Jayalath was concerned. A group of volunteers are now acting to get Jayalath a presidential pardon. The sooner this happens, the better, because it is inhuman to keep this young man in jail. To understand the meaning of this statement, you really have to see how he survives on death row. Words alone aren’t enough to reproduce the full horror of his situation.

He spends most of his time in Bogambara Prison, Kandy, but is sent to Welikada prison in Colombo for two-week stints. It isn’t much of a choice. Death row at Bogambara is hellishly hot with all windows covered, but there are fewer mosquitoes at night due to the milder climate. It is also cleaner than the pest-infested death row at Welikada, though the word hardly seems applicable to the dismal interiors of our overcrowded prisons.

When I visited him in Welikada (since then, he has been transferred to Bogambara prison in Kandy), I had to speak to him through the thick wire mesh which blocked out entry to the dismal interior which houses the prisoners. During the day, they are free to wander about the dimly lit corridors which recall pictures of hellish mental asylums of 19th century Europe. It’s amazing that no one has done any detailed research into the mental and physical health of longterm prisoners in our prisons. It is inevitable that many fall sick or become degenerate under such appalling conditions. The Dehiwela Zoo is hardly a paradise for the caged animals that live in apathy there, but even they seem to be better off than the inmates of our prisons, especially those on death row. At least two ministers of the government, past and present, have spent considerable time in jail, but none have taken the time or trouble even to think of prison reforms once they gained political power.

Society by and large has taken a ‘serves them right’ attitude towards hardcore criminals. Tacit approval for the extrajudicial executions of mafia members and gagsters is widespread across all walks of society. This makes the entire judicial process redundant. At the same time, there is widespread approval of the death penalty, as there is a deep rooted belief that this will deter crime (even though evidence from many parts of the world suggests otherwise). As for those stuffed into our hellish prisons, there is an appalling indifference. As columnist Gamini Wiyangoda recently commented, the phrase ‘prisoners too, are human’ is displayed prominently on the walls of Welikada prison. He sarcastically suggested that this should be displayed inside, not outside.

Our prisons house hardcore criminals along with those sentenced for lesser crimes. In death row, Jayalath, soft-spoken, physically fragile and emotionally vulnerable, must cohabit with rapists and pathological killers. In a civil society, even serial killers are accorded a basic standard of living in prison. They are not left to rot in inhuman, unsanitary conditions. But our prisons, among many other things, lead us to seriously question if ours is a civil society.

Due to the incompetence of the lawyers and the resulting gross miscarriage of justice, Jalayath lost his youth and his future. He could not complete his ordinary level exam. Prison doesn’t allow a death row prisoner to study for an exam. In any case, Jayalath says he has lost his memory and concentration over the years. But he dreams of freedom. Even if he dies as a beggar on the road, he wants to die a free man, and our law and order system, if it has a conscience, is duty bound to let him out now.

Due to the incompetence of the lawyers and the resulting gross miscarriage of justice, Jalayath lost his youth and his future. He could not complete his ordinary level exam. Prison doesn’t allow a death row prisoner to study for an exam. In any case, Jayalath says he has lost his memory and concentration over the years. But he dreams of freedom. Even if he dies as a beggar on the road, he wants to die a free man, and our law and order system, if it has a conscience, is duty bound to let him out now.

Society by and large has taken a ‘serves them right’ attitude towards hardcore criminals. Tacit approval for the extrajudicial executions of mafia members and gagsters is widespread across all walks of society. This makes the entire judicial process redundant. At the same time, there is widespread approval of the death penalty, as there is a deep rooted belief that this will deter crime (even though evidence from many parts of the world suggests otherwise). As for those stuffed into our hellish prisons, there is an appalling indifference. As columnist Gamini Wiyangoda recently commented, the phrase ‘prisoners too, are human’ is displayed prominently on the walls of Welikada prison. He sarcastically suggested that this should be displayed inside, not outside.

Our prisons house hardcore criminals along with those sentenced for lesser crimes. In death row, Jayalath, soft-spoken, physically fragile and emotionally vulnerable, must cohabit with rapists and pathological killers. In a civil society, even serial killers are accorded a basic standard of living in prison. They are not left to rot in inhuman, unsanitary conditions. But our prisons, among many other things, lead us to seriously question if ours is a civil society.